This article gives brief overview of fundamental networking concepts in Kubernetes.

First thing one notices with Kubernetes in comparison to other container orchestration platforms is container itself is not a first class construct in Kubernetes. Containers always exists in the context of pod. So first lets understand the basic Kubernetes building block Pod that consumes network. A pod is a group of one or more containers that are always co-located and co-scheduled, and run in a shared context. The shared context of a pod is a set of Linux namespaces, cgroups etc. Containers within a pod share an IP address and port space, and can find each other via localhost. They can also communicate with each other using standard inter-process communications. Think of it as an application-specific “logical host” containing one or more application containers which are relatively tightly coupled. Containers in different pods have distinct IP addresses and can not communicate by IPC. Please refer to Pod overview for further details. As far as networking is concerned pod is the network endpoint. So essentially Kubernetes networking is all about connectivity between Pods. With that note lets proceed.

Networking functionality in Kubernetes broadly address below problems:

- How cross-node pod-to-pod connectivity (for east-west traffic) is achieved.

- How the services running in the pods are discovered by other pods, and how pod-to-pod traffic is load balanced when consuming a service.

- How services running in the pod’s are exposed for external access from clients outside the cluster (for north-south traffic).

- How with network segmentation, pods are secured by restricting network access to pods

- How high availability, global load balancing etc can be achieved in federated multi-cluster deployments

This article covers first four of above functionalities.

Cross node pod-to-pod network connectivity

While Kubernetes is opinionated in how containers are deployed and operated, it is very non-prescriptive of how the network should be designed in which pod’s are to be run. Kubernetes imposes the following fundamental requirements on any networking implementation (barring any intentional network segmentation policies):

- All pods can communicate with all other pods without NAT

- All nodes running pods can communicate with all pods (and vice-versa) without NAT

- IP that a pod sees itself as is the same IP that other pods see it as

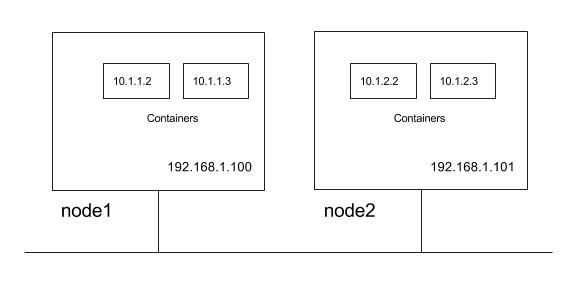

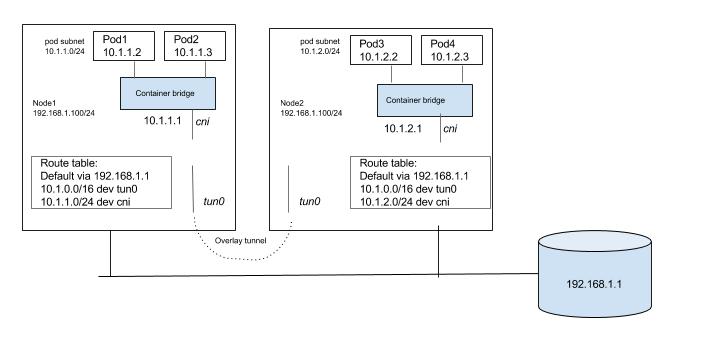

For the illustration of these requirements let us use a cluster with two cluster nodes. Nodes are in subnet 192.168.1.0/24 and pods use 10.1.0.0/16 subnet, with 10.1.1.0/24 and 10.1.2.0/24 used by node1 and node2 respectively for the pod IP’s.

So from above Kubernetes requirements following communication paths must be established by the network.

- nodes should be able to talk to all pods. For e.g. 192.168.1.100 should be able to reach 10.1.1.2, 10.1.1.3, 10.1.2.2 and 10.1.2.3 directly (with out NAT)

- a pod should be able to communicate with all nodes. For e.g. pod 10.1.1.2 should be able to reach 192.168.1.100 and 192.168.1.101 without NAT

- a pod should be able to communicate with all pods. For e.g 10.1.1.2 should be able to communicate with 10.1.1.3, 10.1.2.2 and 10.1.2.3 directly (with out NAT)

As we will explore these requirements lays foundation for how the services are discovered and exposed. There can be multiple way to design the network that meets Kubernetes networking requirements with varying degree of complexity, flexibility.

Network implementation for pod-to-pod network connectivity

Kubernetes does not orchestrate setting up the network and offloads the job to the CNI plug-ins. Please refer to the CNI spec for further details on CNI specification. Below are possible network implementation options through CNI plugins which permits pod-to-pod communication honoring the Kubernetes requirements:

- layer 2 (switching) solution

- layer 3 (routing) solution

- overlay solutions

layer 2 solution

This is the simplest approach should work well for small deployments. Pods and nodes should see subnet used for pod ip’s as a single l2 domain. Pod-to-pod communication (on same or across hosts) happens through ARP and L2 switching. We could use bridge CNI plug-in to reuse a L2 bridge for pod containers with below configuration on node1 (note /16 subnet).

{

"name": "mynet",

"type": "bridge",

"bridge": "kube-bridge",

"isDefaultGateway": true,

"ipam": {

"type": "host-local",

"subnet": "10.1.0.0/16"

}

}

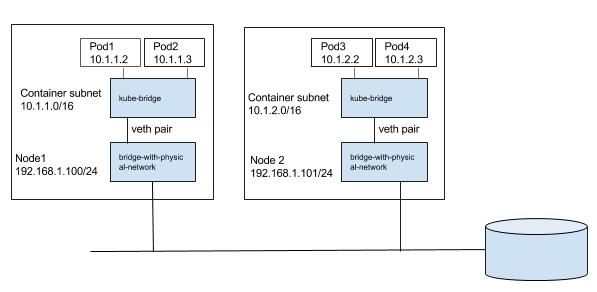

kube-bridge needs to be pre-created such that ARP packets go out on the physical interface. In order for that we have another bridge with physical interface connected to it and node ip assigned to it to which kube-bridge is hooked through the veth pair like below.

We can pass a bridge which is pre-created, in which case bridge CNI plugin will reuse the bridge, only change it would do is to configure gateway for the interface.

layer 3 solutions

A more scalable approach is to use node routing than switching the traffic to the pods. We could use bridge CNI plug-in to create a bridge for pod containers with gateway configured. For e.g. on node1 below configuration can be used (note /24 subnet).

{

"name": "mynet",

"type": "bridge",

"bridge": "kube-bridge",

"isDefaultGateway": true,

"ipam": {

"type": "host-local",

"subnet": "10.1.1.0/24"

}

}

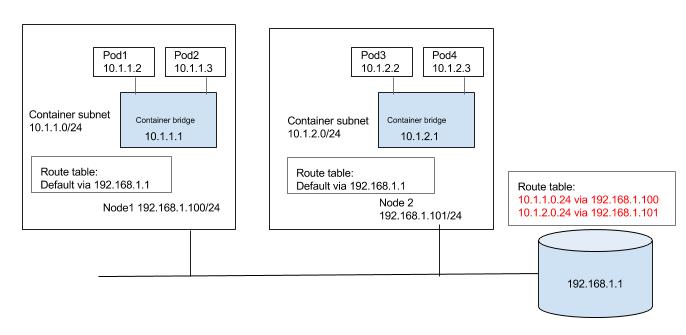

So how does pod1 with ip 10.1.1.2 running on node1 communicate with pod3 with ip 10.1.2.2 running on node2? We need a way for nodes to route the traffic to other node pod subnets.

We could populate the default gateway router with routes for the subnet as shown in the below diagram. Routes to 10.1.1.0/24 and 10.1.2.0/24 are configured to be through node1 and node2 respectively. We could automate keeping the route tables updated as nodes are added or deleted in to the cluster. We can also use some of the container networking solutions which can do the job on public clouds, for e.g. Flannel's backend for AWS and GCE, Weave's AWS-VPC mode, etc.

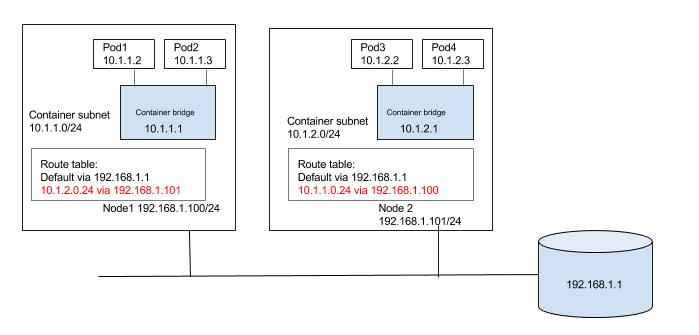

Alternatively each node can be populated with routes to the other subnets as shown in the below diagram. Again, updating the routes can be automated in small/static environment as nodes are added/deleted in the cluster or container networking solutions like calico, or Flannel host-gateway backend can be used.

overlay solutions

Unless there is a specific reason to use an overlay solution, it generally does not make sense considering the networking model of Kubernetes and it's lack of support for multiple networks. Kubernetes requires that nodes should be able to reach each pod, even though pods are in an overlay network. Similarly pods should be able to reach any node as well. We will need host routes in the nodes set such that pods and nodes can talk to each other. Since inter host pod-to-pod traffic should not be visible in the underlay, we need a virtual/logical network that is overlaid on the underlay. Pod-to-pod traffic would need to be encapsulated at the source node. The encapsulated packet is then forwarded to destination node where it is de-encapsulated. A solution can be built around any existing Linux encapsulation mechanisms. We need to have a tunnel interface (with VXLAN, GRE, etc. encapsulation) and a host route such that inter node pod-to-pod traffic is routed through the tunnel interface. Below is very generalized view of how a overlay solution can be built that can meet Kubernetes network requirements. Unlike previous solutions there is significant effort in the overlay approach with setting up tunnels, populating FDB, etc. Existing container networking solutions like Weave, Flannel can be used to setup a Kubernetes deployment with overlay networks.

service discovery and load balancing

With the understanding of Kubernetes network requirements for cross-node pod-to-pod, and node-to-pod communication works, lets explore the critical functionality of service discovery and load-balancing. Any non-trivial containerized application will end up running multiple pods running different services (a web server, DB server, etc.). This leads to a problem: how can some set of Pods running a service provide functionality to other Pods inside the Kubernetes cluster? how does a service consuming pod find out and keep track of which backend pods are providing a service? This problem is compounded by the fact that pods itself can be ephemeral.

services and endpoints

Service abstraction in Kubernetes is an essential building block that helps in service discovery and load balancing. A Kubernetes Service is an abstraction which defines a logical set of Pods based on labels. Labels are key/value pairs that are attached to objects, such as pods. The label selector is the core grouping primitive in Kubernetes that can identify a set of objects with matching labels. Kubernetes services leverage label selectors to group a set of Pods targeted by a Service. Use of labels to group pods to a service significantly eases the management of a service's target pool of pods. Traditionally managing a pool of endpoints or targets for a load balanced service was explicitly done by adding or removing endpoints (for example, adding instance to AWS ELB, GCE load balancer). Kubernetes implicitly manages endpoints of services through the use of labels.

The set of pods forming the service is a dynamic set, so Kubernetes provides the Endpoints abstraction for the service, which gives the list of the pod's IP:PORT that match the service's label selector at the time of inquiry.

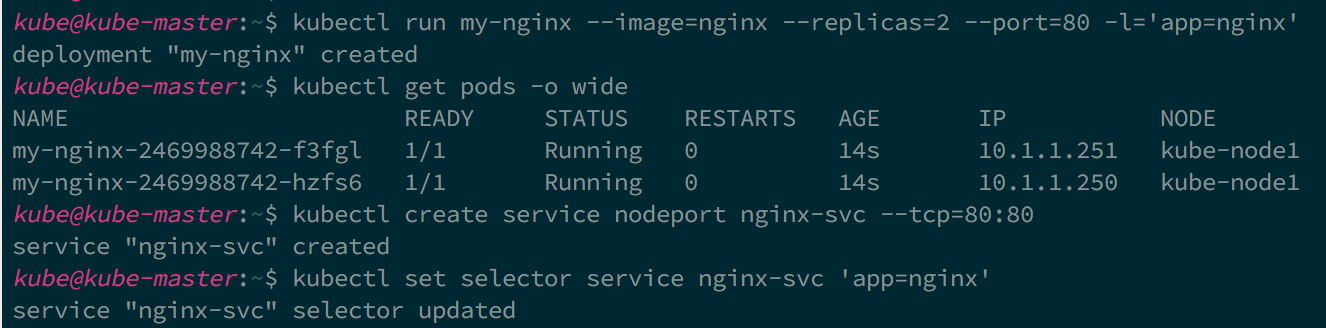

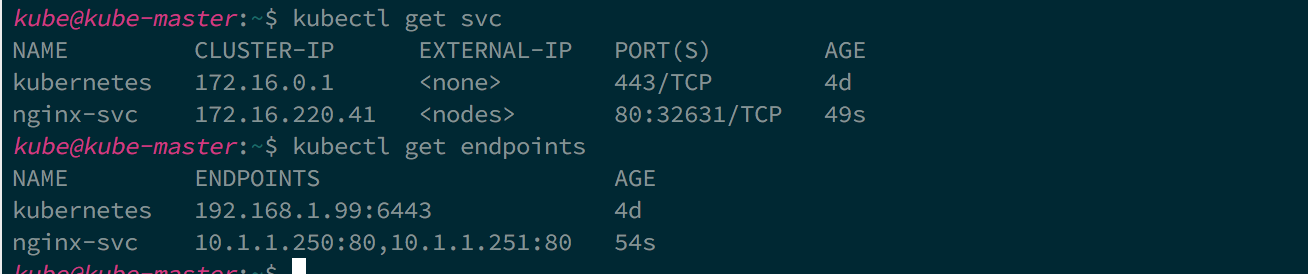

Lets walk through an example. In the below example first we created 2 pods each marked with label ‘app=nginx’ and expose port 80. We created a service with selector matching labels ‘app=nginx’.

As you can see both the pods selected as endpoints for the service.

exposing service

A pod that wants to consume a service can get the list of endpoints and do client side load balancing to manage how and to which endpoint it connects. The most common case however is server-side load balancing where a service's endpoints are fronted by virtual ip and load balancer that load balances traffic to the virtual ip to it's endpoints. The concept of load balancing traffic to a service's endpoints is provided in Kubernetes via the service's definition. Kubernetes allows several different service types. The following are the service types and their behaviors:

- ClusterIP: A service of ClusterIP type exposes the service on a cluster-internal IP. Choosing this value makes the service only reachable from within the cluster. Cluster internal IP is allocated from the cluster CIDR for the service, and acts as a VIP on each node that can be reached by the pods. Cluster IP is not routable, and can be reached only by the pods running on the node.

- NodePort: Exposes the service on each Node’s IP at a static port (the NodePort). You’ll be able to contact the NodePort service, from outside the cluster.

- LoadBalancer: Exposes the service externally using a cloud provider’s load balancer. NodePort and ClusterIP services, to which the external load balancer will route, are automatically created.

Both ClusterIP and NodePort service types are expected to create a service proxy on the node, which can be accessed by the pods running on the node in case of ClusterIP and accessed from the cluster in case of NodePort. Service proxy load balances traffic to the appropriate endpoint of the service. Hopefully this explains the network requirements of Kubernetes that we discussed earlier where a pod can reach a node and vice versa.

service discovery

Kubernetes API provides all the details about the service, but how do pods learn the details of the service? Kubernetes supports two primary modes of finding a Service. When a Pod is run on a Node, the kubelet adds a set of environment variables for each active Service with pre-defined convention on the environment variable names. The alternative is to use the built-in Kubernetes DNS service which can be added as an add-on to the cluster. The DNS server watches the Kubernetes API for new Services and creates a set of DNS records for each. If DNS has been enabled throughout the cluster then all Pods should be able to do name resolution of Services automatically.

kube-proxy

Kube-proxy is core component of Kubernetes running on each node, that uses iptables to provide a service proxy. Kube-proxy configures iptables such that both ClusterIP and NodePort are available as services on the node for the pods. Traffic is not exactly load balanced but distributed equally to the endpoints of the service. Kube-proxy provides only L4 load balancing. Kube-proxy itself is not a mandatory component and is replaceable. It provides an out-of-box service proxy solution. If you want L7 load balancing between the services, or use true load balancer like HAproxy or Nginx there are community solutions (for e.g. Linkerd) that are available.

Ingress resource and Ingress controller

While the Kubernetes abstraction of services provide a discovery and internal load balancing for the pods within the cluster, we need a way to expose the service externally to the internet (north-source traffic). An Ingress abstraction in Kubernetes is a collection of rules that allow inbound connections to reach the cluster services. Ingress abstraction only gives a mechanism to define the rules, but you will need an implementation of these rules, known as ‘Ingress Controlles’. Kubernetes does not come with an out-of-box Ingress Controller but there are third party solutions like Traefik and Nginx available. Ingress controller also provide L7 load balancing unlike cluster services.

Network policies

We have learned so far how pods can communicate with each other directly or through service proxy. We also learned how pods through services get exposed externally outside the cluster. Now the logical question is how do we secure pods? A Network Policy in Kubernetes is a specification of how subsets of pods are allowed to communicate between each other and other network endpoints.

Isolation policies are configured on a per-namespace basis. Once isolation is configured on a namespace it will be applied to all pods in that namespace. Currently only the ‘DefaultDeny’ policy is configurable on a namespace. Once configured, all ingress to the pods in the namespace is blocked. You need to explicitly configure whitelisting rules through the network policies to authorize ingress to those pods. Network policies leverage the Kubernetes concept of labels to provide an elegant way of expressing application security intents. For example, below network policy concisely express the intent that only pods with matching label of ‘role: frontend’ can access the pods with matching label of ‘role: db’ on port 6379 in that namespace.

apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1

kind: NetworkPolicy

metadata:

name: test-network-policy

namespace: default

spec:

podSelector:

matchLabels:

role: db

ingress:

- from:

- namespaceSelector:

matchLabels:

project: myproject

- podSelector:

matchLabels:

role: frontend

ports:

- protocol: tcp

port: 6379

Conclusion

We have covered how the cross-node pod-to-pod networking works, how services are exposed with in the cluster to the pods, and externally. What makes Kubernetes networking interesting is how the design of core concepts like services, network policy, etc. permit several possible implementations. Though some core components and add-ons provide default implementations, they are replaceable. There is a whole ecosystem of network solutions that plug neatly into the Kubernetes networking semantics. In kube-router blog we will walk through a solution for Kubernetes that provides cross-node pod-to-pod networking, service proxy and ingress firewall for the pods.